News

The dangers of deep discounts

Many claim discounting is a necessary evil in the pizza business, but experts say prices don't have to be dramatically low to be competitive. The numbers prove that discounting too deeply for too long can kill your business.

October 9, 2005

The message is a familiar one heard by Kamron Karington, a marketing consultant to pizza operators: "I'm busy, but I'm broke. I can't make any money in this business."

Karington, a former four-unit pizza operator, speaks regularly at industry events attended by pizzeria owners who are close to throwing in the towel. Just to stay in business, they've entered the discount wars, slashed prices to compete and simultaneously torpedoed their profits. He likened them to hamsters on a wheel running nowhere fast, struggling to keep pace with chains that can cut prices and still make money.

The solution? Get out of the price war, he said, because it's unlikely you'll win. It also could crush your business.

"I tell people like them that you can sell your product or you can slash your price," said Karington, author of the pizzeria marketing tome, The Black Book. "Selling your product is a little tougher, but it's the only long-term solution to making money in this business. You'll lose if all you do is discount."

But how do you do that when Pizza Hut hawks medium Pan Pizzas for 25 cents and the Domino's 5-5-5 steamroller is flattening your market share? The only way for operators to fight back, Karington said, is to use other weapons in their business arsenals. When they promote their businesses' uniqueness and serve customers in ways their competitors don't, it

|

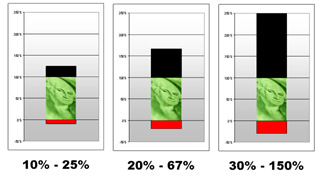

The graph on the far left shows that an operator who discounts his prices by 10 percent has to increase his transaction counts by 25 percent to make the same profit. The subsequent graphs show that the need to increase transactions rises exponentially as the discounts deepen. |

"Independents can't keep up with the Domino's or the Little Caesars of the world, so they've got to find their niche and appeal to customers in different ways," said Jeff Pappas, managing director for Acceleron Group, a Las Vegas-based business and financial advisory service for restaurant companies. "Independents have to compete on quality of product, service and execution."

The math will frighten you

Karington said some simple math will open the eyes and drop the jaws of many who are in the thick of the discount battle. For example, if the owner of a pizzeria discounts his product by just 10 percent, he'll need a 25 percent increase in transactions to offset that discount.

"So if you had 100 customers last night, and tonight you're going to give a 10 percent discount, you're going to need 125 customers to make the same money you made the night before," Karington said. At 20 percent off, that same operator will need a 67 percent increase in business. At 30 percent off, the requirement soars to 150 percent.

"In my experience, a 10 percent discount doesn't even register a blip on anybody's radar screen," Karington said. "And if you need 150 percent more business to offset a 30 percent discount, I can assure you that will never happen."

And yet, many operators discount even deeper than 30 percent in trying to keep pace with the industry's price-slashing powerhouses. Thinking they have to overthrow Little Caesars or topple Domino's leads them to overlook the fact that those chains have unparalleled buying power and cavernous advertising coffers. Razor-thin margins on $5 pizzas will replace cash with cobwebs in an independent's till, but they aren't a problem for chains that sell millions of them every day.

Jay Siff, co-founder of Moving Targets, a Perkasie, Pa.-based direct mail firm, said too few independents look closely enough at the numbers to know the dangers of discounting. "Does the little guy really know how to do the math and figure out the return on investment on what he does? I don't think so." Not calculating the cost ahead of time draws many operators deep into the red, he said.

Be nimble

In most cases, trying to run an independent business like a chain business is smart, Pappas said. Having clearly defined methods for preparation, production, tracking and accounting is invaluable to the bottom line.

But where independents should excel is where chains can't: in their ability to make quick, creative decisions that address market conditions both proactively and reactively. He said too few independents exercise their freedom to make adjustments on the fly, such as adding new menu items and creating unusual specials — things few

|

|

|

"Small companies can be more nimble, and that's a competitive advantage they have to use," he said.

Instead of matching competitors discount for discount, Karington suggested using low-cost giveaways of items like salads, desserts, appetizers or breadsticks. Freebies, he said, have stronger appeal to customers than $2 off a pizza, and they generate product trial in non-pizza areas of the menu.

"If you give away a free order of wings, and wings are five bucks, the customer sees a free $5 item, which costs you maybe a $1.50 to make," he said. "But if you discount a pizza by a $1.50, the customer sees only a $1.50 off. Human beings are much more motivated by gaining an add-on item than they are by saving $1.50."

Mike McManama, vice president of marketing, research and development for 170-unit Papa Gino's Pizza, said that company decided two years ago to abandon deep discounting because it yielded only temporary gains, not loyal customers.

"In a category like pizza, which is basically flat, deep discounting only becomes a market-share war that nobody really wins," said McManama, whose company is in Dedham, Mass. "Offering deep discounts is not going to win customers in the long term. You have to offer more value beyond just a discounted price to keep your customers."

Papa Gino's is big on bundling, he said, including simple, uniquely named offers geared toward small and large groups. Customers who buy the bundled meals get a bonus: posters of sports stars from the New England Patriots and the Boston Red Sox.

"By giving away posters with bundled meals, which we call Kickers, we're offering more value," McManama said. Kickers are two-pizza meals that come with choice of a free salad, fried cheese sticks or cinnamon bread sticks. "To us, that's a reward that's unique, but not very costly — not nearly as costly as a deep discount."

But don't abandon discounting

Jeff Loudin, eastern regional vice president for Money Mailer, a Garden Grove, Calif., couponing company, said discounts are a vital part of the foodservice game because of the high level of quality and competition in the marketplace. Consumers love the myriad choices available to them, so incentives to get them to try yours must be powerful.

Still, Loudin

— Kamron Karington, |

"If you get them to try it once, and your product's good, they'll get hooked," he said. "And if you give them consistent quality, they'll come back and pay the regular price. But if you're selling garbage, you can give stuff away and they'll say, 'I'm not going to go there.'"

Operators cut their throats with low-ball offers, he said, when they could get the same business with an offer that benefits them as well.

"Let's say your restaurant's check average is $25," he began. "Then make an offer to give customers $5 off every purchase of $25 or more." The restaurant does well because customers pay nearly what they typically do, and customers win because they get a reward for their loyalty.

Such offers are smart ones, said Siff, because they don't condition customers to get something for nothing. Even more encouraging, he said, is the fact that such an offer demonstrates an operator who is thinking seriously about making money and winning long-term customers.

"If you just shotgun out offers without any idea of how to measure it, you're just throwing money away," he said. "But if you apply discounting judiciously, you can make money at it."